This Lent I’ve been writing tongue-in-cheek on the number 42, “the Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything,” (from “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy” by Douglas Adams). Thus, this Lenten series is exploring the forty-second chapters of the Bible. Psalm 42 went well; I love the psalms, anyway. Genesis 42 was more of a struggle, particularly because it was a middle chapter in Joseph’s story. Job 42, however, is the end of Job’s story. It’s the last chapter in the book of Job. This is the resolution to the many trials and tribulations of Job.

Job (pronounced with a long ‘o’, so that it rhymes with ‘robe’) has been referred to as the most depressing book in the bible. Some folks can’t stand it because they feel like God comes across as a jerk instead of loving, kind, and merciful. Job is also the Bible story most cited when people feel like absolutely nothing is going their way, everything is falling apart, and they have nothing left. I’ve heard it from patients in the hospital: “I feel like Job. I have no one and now not even my health.”

The short version of the story of Job (which is 42 chapters long) is that God and Satan make a deal. Job is “blameless and upright, one who feared God and turned away from evil.” Satan says Job’s moral character is because God has protected him and blessed him; Job’s never had a reason to curse God. God responds that God will remove his protection from Job and Satan will be free to act against Job as long as he does not kill him. So, all of Job’s children die, his livestock (Job was a farmer) all die, and Job gets sick. In all this tragedy, Job still does not blame God, although Job’s wife does. Then, three of Job’s friends show up. They sit with him in silence, in his grief, for seven days. Unfortunately, then the friends start talking, and they all say that Job must have done something to deserve this punishment. Job even curses his birth and his life but does not curse God. There are extensive monologues by Job and each of the three friends, as the friends blame Job while he maintains his innocence. Finally, in chapter 38, God speaks up and reminds Job and his friends that they do not know all the intricacies of creation; they are not God.

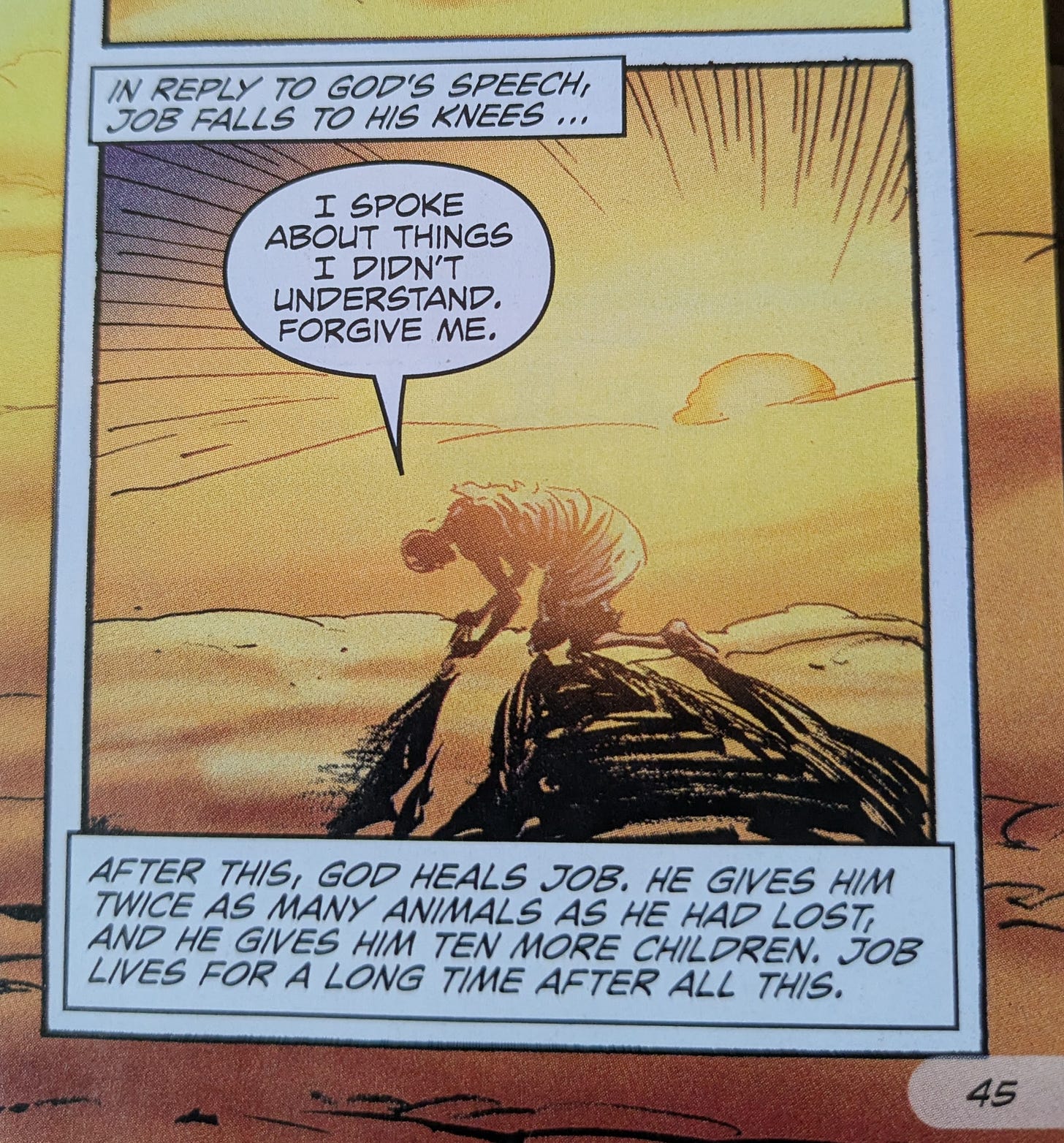

In chapter 42, Job gives a brief response to God, “I know that you can do all things and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted… Therefore, I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me that I did not know… I had heard of you by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees you; therefore I … repent in dust and ashes.” It’s a good Lenten response, generally, and Ash Wednesday in particular. It’s the reminder that we are mortal; we are not God. We overstepped, thinking and speaking and acting like we were God, and now we repent in dust and ashes. God forgives the friends, and Job’s fortunes are restored, double what they were before.

Job shows a way to question God, to doubt God, and yet to remember that we are mortal. We are created beings, in God’s image, yes, but not God. We are in relationship with God and I believe God welcomes our questions and doubts. That’s part of what makes it an open and honest relationship. Querying, clarifying, discerning, wondering; these are all things we do with our friends, families, and coworkers. We do not take the place of any of these people, however. We may identify with or empathize with their situation. However, we also self-differentiate; that is, we know who we are individually and we maintain our own sense of personhood in the relationship. We are God’s beloved, in relationship with God, and we self-differentiate to know what God’s work is, and what is our work.

Thinking that we are God, that we are self-made, is one of the more common traps in our American capitalistic society. When we find ourselves acting this way, it is time to repent, which means to turn back to God. We remember that God is God, and we are not. We stand on the shoulders of those who came before us, but no more holy or worthy than our ancestors. We wrestle with God, just like they did, and “fight the good fight.” At the end of the day, God is the Almighty One, the potter, and we are the clay.